News

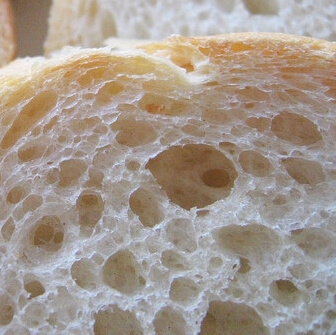

Harvard engineering: born and bread. Rumford Baking Powder was invented by Eben Norton Horsford, who held the Rumford professorship at Harvard. Photo courtesy of Flickr user Niina C.

Baking, whether breads, cakes, or muffins, is ultimately about the bubbles.

More than 150 years ago, a Harvard professor figured out how to put the bubbles into bread, making a lasting contribution to both the culinary arts and the pantries of modern kitchens through baking powder.

For millennia, the bubbles that gave bread and other baked goods their light texture came from yeast, which gives off carbon dioxide when mixed with flour and water. The gas forms bubbles in the dough, which expand on baking.

In the 1800s, the search was on for a way to make bread that didn’t require the hours that yeast takes to work. Harvard chemist Eben Norton Horsford hit on the right combination.

Horsford was the Rumford Professor of the Application of Science to the Useful Arts, and was among the first faculty members at the precursor to Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), the Lawrence Scientific School. Horsford arrived at Harvard the same year the School began, 1847, and his appointment was transferred to the School on its creation. He also served as Lawrence Scientific School’s dean for several years.

Horsford took the “useful arts” in his title seriously, and much of his research applied to practical, everyday matters. Over the years, he examined the best metal to use for Boston’s water pipes. He created a compact “marching ration” for the army in the Civil War. And he developed a process for making condensed milk that was used on an expedition to explore the Arctic and was then sold to the Borden company.

But baking powder has proven his most lasting legacy. Earlier bakers had tried different formulations to substitute for yeast, but each had drawbacks, according to a history posted on the American Chemical Society’s website. Most of those formulations included sodium bicarbonate, baking soda, which creates carbon dioxide gas when combined with an acid and water. Common formulas used sour milk or cream of tartar as the acid, but varying levels of acidity in the milk and an unreliable supply of cream of tartar made neither substitute ideal.

Horsford began working on the problem in 1854 and came up with acombination of acid phosphate and sodium bicarbonate. He eventually added a bit of corn starch to keep the product dry until used.

Horsford partnered with George Wilson to found the Rumford Chemical Works in East Providence, R.I., named after Count Rumford, the benefactor who endowed his chair at Harvard. Horsford marketed his baking powder formula as Rumford Baking Powder, which is still sold today.

The advance was recognized as a milestone in America’s chemical history by the American Chemical Society in 2006. The society named the Rumford Chemical Works’ East Providence site a National Historic Chemical Landmark, with the citation: “As a result of Horsford’s work, baking became easier, quicker, and more reliable.”

Though the Lawrence Scientific School eventually disappeared, Horsford’s successors are at work today in the classrooms of Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, where faculty members are examining the science behind recipes in their “Science of Cooking”class.

Michael Brenner, Glover Professor of Applied Mathematics and Applied Physics and an instructor in the class, said that while “food science” programs at other institutions are typically focused on health and nutrition, both Horsford and the “Science of Cooking” class share an approach that seeks to understand the science behind food.

The class, Brenner said, was inspired by some of today’s top chefs,such as Ferran Adrià, who use a deep understanding of why recipes work to create new foods. Foam, for example, is normally created by beating egg whites, but retains the eggy flavor. Adrià created a model by using only the part of the white that creates foam, a substance called lecithin. This removes the egg taste and allows added flavors to shine through.

“Baking powder allowed food to be made that was never made before,” Brenner said. “I think you could argue that this [class] is in the tradition of Horsford.”

As Harvard celebrates its 375th anniversary, the Harvard Gazette is examining key moments and developments over the University’s broad and compelling history. To read the full article, click here.

Topics: Applied Physics

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Michael P. Brenner

Michael F. Cronin Professor of Applied Mathematics and Applied Physics and Professor of Physics