News

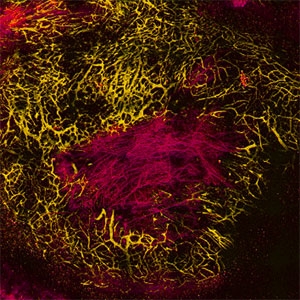

In many solid tumors blood vessels are collapsed, limiting drug delivery and efficacy of a number of cancer therapies, including chemotherapy. Blood vessels (shown in gold) are compressed by components of the extracellular matrix (shown in crimson). Targeting these components can open blood vessels to enhance chemotherapy. (Image courtesy of Vikash Chauhan, Steele Lab for Tumor Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital.)

Boston, Mass - October 1, 2013 - Use of existing, well-established hypertension drugs could improve the outcome of cancer chemotherapy by opening up collapsed blood vessels in solid tumors, according to researchers based at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH).

The team reported their findings in the journal Nature Communications, with Vikash P. Chauhan (S.M. '08, Ph.D. '12), a former graduate student at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), as co-lead author. Chauhan contributed to the research while earning his doctoral degree in engineering sciences.

In their report, the investigators describe how the angiotensin inhibitor losartan improved the delivery of chemotherapy drugs and oxygen throughout tumors by increasing blood flow in mouse models of breast and pancreatic cancer. A clinical trial based on the findings of this study is now underway.

"Angiotensin inhibitors are safe blood pressure medications that have been used for over a decade in patients and could be repurposed for cancer treatment," explains Rakesh K. Jain, director of the Steele Laboratory for Tumor Biology at MGH and senior author of the study. "Unlike anti-angiogenesis drugs, which improve tumor blood flow by repairing the abnormal structure of tumor blood vessels, angiotensin inhibitors open up those vessels by releasing physical forces that are applied to tumor blood vessels when the gel-like matrix surrounding them expands with tumor growth."

Focusing on how the physical and physiological properties of tumors can inhibit cancer therapies, Jain's team previously found that losartan improves the distribution within tumors of relatively large molecules called nanomedicines by inhibiting the formation of collagen, a primary constituent of the extracellular matrix. The current study looked at whether losartan and other drugs that block the action of angiotensin—a hormone with many functions in the body—could release the elevated forces within tumors that compress and collapse internal blood vessels. These stresses are exerted when cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)—specialized cells in the tumor microenvironment—proliferate and produce increased levels of both collagen and a gel-like substance called hyaluronan.

The team's experiments in several mouse models showed that both collagen and hyaluronan are involved in the compression of blood vessels within tumors and that losartan inhibited production of both molecules by CAFs through reducing the activation and overall density of these cells. Compared with drugs called ACE inhibitors, which block angiotensin signaling in a different way, losartan and drugs of its class—termed angiotensin receptor blockers—appeared better at reducing compression within tumors. In models of breast and pancreatic cancer, treatment with losartan alone had little effect on tumor growth, but combining losartan with standard chemotherapy drugs delayed the growth of tumors and extended survival.

"Increasing tumor blood flow in the absence of anti-cancer drugs might actually accelerate tumor growth, but we believe that combining increased blood flow with chemotherapy, radiation therapy or immunotherapy will have beneficial results," explains Jain, who is also the Cook Professor of Radiation Oncology (Tumor Biology) at Harvard Medical School. "Based on these findings in animal models, our colleagues at the MGH Cancer Center have initiated a clinical trial to test whether losartan can improve treatment outcomes in pancreatic cancer." Information on this trial is available at http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01821729.

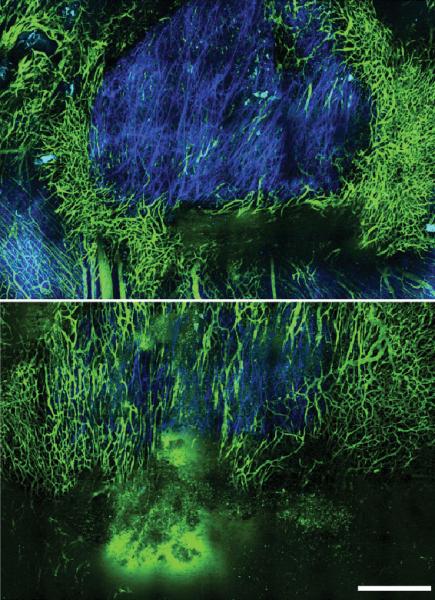

Top image: Before treatment with the angiotensin inhibitor losartan, stresses within a tumor caused by the buildup of collagen (blue) compress blood vessels and restrict blood flow (green). Bottom image: After losartan treatment, blood vessels open up, restoring the blood flow required for effective chemotherapy. (Vikash Chauhan, Steele Lab for Tumor Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital.)

John D. Martin, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology doctoral student currently part of Jain's team, was co-lead author of the report in Nature Communications. Additional coauthors were Hao Liu, Delphine Lacorre, Saloni Jain, Sergey Kozin, Triantafyllos Stylianopoulos, Ahmed Mousa, Xiaoxing Han, Pichet Adstamongkonkul, Peigen Huang and Yves Boucher, Steele Lab; and Zoran Popović and Moungi Bawendi, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The study was supported primarily by National Cancer Institute grants P01-CA080124, R01-CA126642, R01-CA085140, R01-CA115767 and R01-CA098706, and by Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program Innovator Award W81XWH-10-1-0016. The MGH and Xtuit Pharmaceuticals, a company co-founded by Jain, have applied for a patent based on the work described in this paper.

###

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The MGH conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, with an annual research budget of more than $775 million and major research centers in AIDS, cardiovascular research, cancer, computational and integrative biology, cutaneous biology, human genetics, medical imaging, neurodegenerative disorders, regenerative medicine, reproductive biology, systems biology, transplantation biology and photomedicine.

Adapted from an original release by Sue McGreevey, Massachusetts General Hospital.

Topics: Bioengineering

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Caroline Perry