News

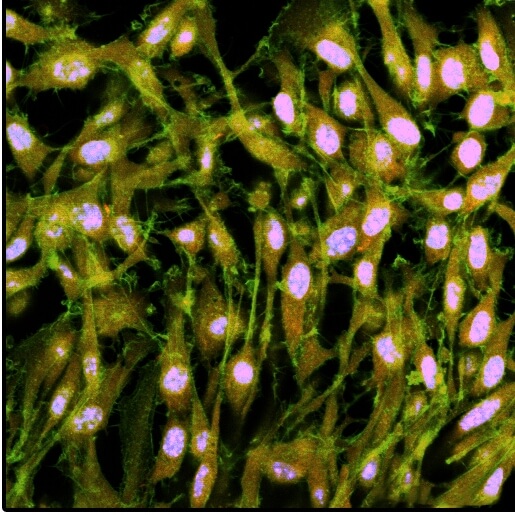

A mesenchymal stem cell sheet that has been grown on the switchable oil-infused, fibronectin-coated polymeric matrix, transferred with the method to a new surface and stained for markers. (Image courtesy of the Aizenberg Lab/Harvard University)

Transplanting a preformed dense and coherent sheet of regenerative stem cells directly onto damaged heart, cartilage or bone tissue of ailing patients often is a more promising route to recovery than transplanting the cells just loosely mixed together. The challenge in obtaining intact cell sheets, however, lies in releasing them from the substrate they are grown on in the culture dish quickly and without affecting their efficiency. Current methods to detach intact transplantable cell sheets from their growth surfaces in the culture dish require manipulations like a shift in temperature that can impact the efficiency of finicky cell types suitable for specific treatments and be prohibitively expensive for developing new applications.

As reported on 18 May in Scientific Reports, Joanna Aizenberg’s team at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University has developed a new method that can induce slipperiness on a growth supporting surface at will and sets the stage for the fast, efficient and inexpensive recovery of intact sheets of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with broad potential for regenerative medicine.

Earlier work by Aizenberg was based on the observation that the Nepenthes pitcher plant, in times of rain, can reversibly render its surface slippery enabling it to trap insects. This ability in mind, Aizenberg’s team pioneered Slippery Liquid-Infused Porous Surfaces (SLIPS) as a general anti-fouling strategy.

“We leveraged these same basic principles that drove our previously conceived SLIPS, in which a thin oil layer formed on a polymeric matrix repels unwanted substances and organisms including ice, blood, bacteria or crude oil from a surface. In our new study, we use those principles as a ‘creative’, rather than ‘preventive’, strategy to generate a switchable surface in which we can induce slipperiness and release at will, at a time when an intact cell sheet with regenerative capacities has formed on the surface,” said Aizenberg, the Amy Smith Berylson Professor of Materials Science and a Core Faculty member at the Wyss Institute.

As the method’s linchpin, the team generated a thin layer of the commonly used, biocompatible polymeric material polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) in a cell culture dish that was infused with a chemically matched, non-toxic silicone oil to saturation. In addition, the infused polymer was coated with human fibronectin (FN), an extracellular matrix protein that MSCs and other cell types able to repair damaged tissues can adhere to and proliferate on in their natural tissue environments or in culture conditions.

“Once we have grown a near-confluent sheet of cells on top of the oil-infused, FN-coated polymer, we can carefully inject a small amount of oil underneath the cell layer. Because the polymer itself is already saturated, the oil can be freely moved around as a pool to detach the entire sheet including its adherent FN substrate in only about five minutes, much more rapidly than other methods would allow. Using a filter paper, we then are able to transfer the cell sheet to a new surface that in the future could be replaced by target tissues for in vivo regenerative approaches,” said Nidhi Juthani, a Visiting Student working with Aizenberg and the first author on the study.

Aizenberg’s team, co-led by Wyss Technology Development Fellow Caitlin Howell (now Assistant Professor at the University of Maine), is working to further tailor and automate the procedure. Their goal is to facilitate the engineering of more differentiated cell sheet products such as muscle tissue or cartilage, and enable higher throughput generation and testing of multiple standardized cell sheets in parallel.

“Our technology is highly tunable: by changing the elasticity and geometry of the oil-infused polymer and adding in tissue-specific extracellular matrix proteins and differentiation factors that then become integral to the cell sheet, we may be able to tailor it to the engineering of diverse cell sheets suitable for various regenerative processes. This versatility, low cost and simplicity have not been possible with existing methods,” said Aizenberg.

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Joanna Aizenberg

Amy Smith Berylson Professor of Materials Science and Professor of Chemistry & Chemical Biology

Press Contact

Leah Burrows | 617-496-1351 | lburrows@seas.harvard.edu