News

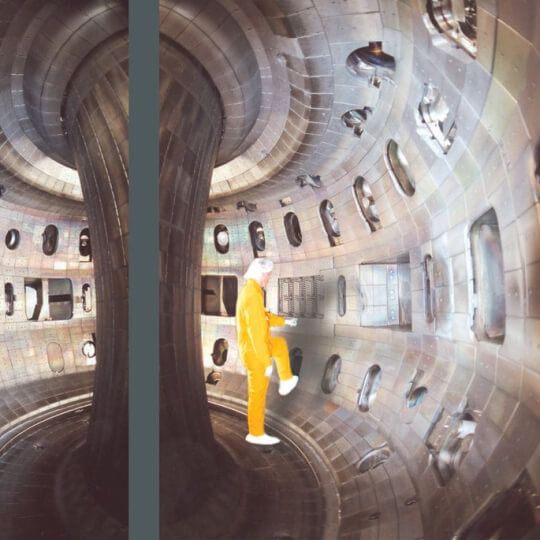

While no fusion reactors are net producers of power yet, a finding about instability in materials surfaces may lead to the design of improved structural materials for plants. (Image courtesy of ITER.)

Cambridge, Mass. – April 12, 2011 – A new discovery about the dynamic impact of individual energetic particles into a solid surface improves our ability to predict surface stability or instability of materials under irradiation over time.

The finding may lead to the design of improved structural materials for nuclear fission and fusion power plants, which must withstand constant irradiation over decades. It may also accelerate the advent of fusion power, which does not produce radioactivity.

SUN IN A BOTTLE

Fusion, also known as "sun in a bottle," re-creates on earth the sun's nuclear process for converting hydrogen into helium in a plasma.Unlike all nuclear power plants operating today, which are based on fission—the breaking up of heavy nuclei into lighter ones—fusion consumes only water and creates no radioactive waste.While no fusion reactors are net producers of power yet, both the U.S. and Europe have built demonstration reactors.

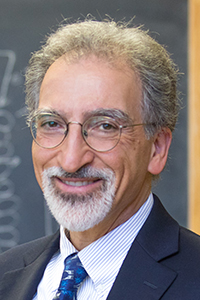

Publishing in Nature Communications, Michael Aziz, Gene and Tracy Sykes Professor of Materials and Energy Technologies, and Michael Brenner, Glover Professor of Applied Mathematics and Applied Physics, both at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and colleagues developed a new rigorous mathematical theory that is "fed" the measured shape of the average crater resulting from the impact of an energetic particle.

The impacts, lasting a few trillionths of a second, are simulated using intensive computer calculations. The theory then "up-scales" the cumulative effect of individual energetic particle impacts to predict surface topography evolution over thousands of seconds or longer.

"Our results illustrate how large-scale computer simulations can be combined with rigorous mathematical analysis to yield precise predictions of new phenomena on length and timescales that would otherwise be computationally impossible,” says Brenner.

The researchers were surprised to discover that stability/instability is not determined by the atoms that are blasted away, but instead by the atoms that are knocked around and re-settle nearby.

“Our discovery overturns a long-held paradigm about what causes surfaces to erupt into patterns under energetic particle bombardment. The blasting away of individual atoms from energetic particle impacts has long been thought to determine whether a surface is stable or unstable," says Aziz.

"The effect of atoms blasted away turns out to be so small that it is essentially irrelevant. The lion’s share of the responsibility of what makes a surface stable or unstable under irradiation comes from the cumulative effect of the much more numerous atoms that are just knocked to a different place but not blasted away."

The team found that the cumulative effect of these displacements can be either ultra-smoothening, which may be useful for the surface treatment of surgical tools, or topographic pattern-forming instabilities, which can degrade materials. The outcome depends on the type of material, energetic particle, and irradiation conditions.

The discovery, while interesting in its own right, may also help to solve a mysterious degradation problem in tungsten plasma-facing reactor walls in prototype fusion reactors.

Tungsten is used for two reasons. First, it is inert to nuclear reactions that could arise from the bombardment by hydrogen and helium from the plasma. Additionally, Aziz says, "The material is so strongly bound that this bombardment does not lead to the blasting away of any tungsten atoms."

Yet, under some conditions the tungsten inexplicably becomes “foamy” or begins to degrade.Armed with insight from the new theory, the researchers considered the implications for foamy tungsten.

“Even under plasma conditions where no tungsten atoms are blasted away, they are indeed displaced to new positions,” says Aziz. “We conjectured that the way the helium moves the tungsten atoms around is causing the instability. While more research will be needed to know for sure, we think we're finally in the position of being able to develop a predictive theory for tungsten by extending the one we have presented here for simpler materials.”

Extending the study to more complex materials such as tungsten is an important future challenge, as it could lead to better design criteria for materials that must remain stable during exposure to irradiation, both for cleaner, safer fusion and for conventional fission reactors.

Aziz and his colleagues developed an experimental data set using ion beam irradiation of silicon because it is the simplest prototype material for such studies. Their theory was validated by detailed comparison of its predictions to their experimental results for surface ultra-smoothening, instabilities, and pattern formation in silicon.

“This could help solve a technical problem with nuclear fusion power, which holds promise for nuclear power without radioactivity,” says Aziz.

Co-authors included Scott A. Norris, a former postdoctoral research fellow in SEAS and now on the Faculty at Southern Methodist University; Juha Samela, Larua Bukonte, Marie Backman, Djurabekova Flyura, Kai Nordlund, all at the Department of Physics and Helsinki Institute of Physics; and Charbel S. Madi, a Ph.D. student in SEAS.

The research was supported by the Department of Energy; the National Science Foundation (NSF); the NSF-funded Materials Research Science and Engineering Center at Harvard; the Kavli Institute for Bionano Science and Technology at Harvard; and the Academy of Finland and the University of Helsinki. The authors also acknowledge grants of computer time from the Center for Scientific Computing in Espoo, Finland.

Topics: Materials, Environment, Applied Mathematics

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Michael P. Brenner

Catalyst Professor of Applied Mathematics and Applied Physics and of Physics

Michael J. Aziz

Gene and Tracy Sykes Professor of Materials and Energy Technologies