News

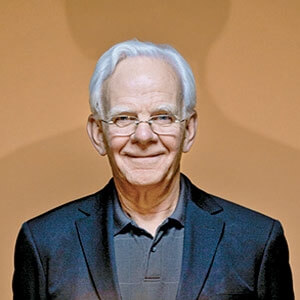

Jim Anderson is the winner of a 2012 Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award for his contributions to atmospheric science. (Image courtesy of Smithsonian.)

The following is an excerpt from an article by Sharon Begley appearing in the December 2012 issue of Smithsonian magazine. Professor James Anderson is the winner of a 2012 Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award; the article and this video celebrate his contributions to atmospheric science and our understanding of the Earth's climate.

The ozone problem is back—and worse than ever.

“Bull!” said Kerry Emanuel, an atmospheric scientist at MIT.

Jim Anderson of Harvard University was showing him some weird data he had collected. Since 2001, Anderson and his team had been studying powerful thunderstorms by packing instruments into repurposed spy planes and B-57 bombers, among the only planes capable of flying into the storms “without having their wings ripped off,” Anderson said. To his puzzlement, the instruments detected surprisingly high concentrations of water molecules in the stratosphere, the usually drier-than-dust uppermost layer of the atmosphere. They found the water over thunderstorms above Florida, and they found it over thunderstorms in Oklahoma—water as out of place as a dolphin in the Sahara.

While water in the stratosphere might seem innocuous, the finding made Anderson “profoundly worried,” he recalls. From the decades he had spent studying the depletion of the earth’s ozone layer—the thin gauze of molecules in the stratosphere that blocks most incoming ultraviolet radiation—Anderson knew that water could, through a series of chemical reactions, destroy ozone.

It was when he told Emanuel that violent thunderstorms seemed to be heaving water high into the atmosphere that his MIT colleague expressed his skepticism. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation showed “you’d need an updraft of 100 miles an hour” to do that, Emanuel said. Impossible.

Anderson persisted.

Read the entire article in Smithsonian.

To learn more about the winners of the 2012 Smithsonian American Ingenuity Awards, click here.

Topics: Environment, Climate

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

James G. Anderson

Philip S. Weld Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry